In the animal kingdom, humans reign supreme. Since we don’t have especially sharp teeth or ferocious roars, we possess the mental prowess to make rational and calculated decisions. But is that true? While we want to believe that us humans are sitting in the mind's driver’s seat, several factors exist that dispute our ability to make rational decisions.

Before becoming discouraged by the prospect of not being able to reason rationally, keep reading to better understand how your brain works and processes information. By learning what shapes your choices, you might just be able to make better decisions.

The Quickest Conclusion is Not Always the Most Rational

Who has a more dangerous job, a police officer or a logger? If you guessed a police officer, you are exercising availability heuristic, a thinking method that relies on the frequency of events in the world by the ease with which examples come to mind. Brains depend on availability heuristic to sift through all the information floating in our heads. When making decisions, we trust our mind to provide us with the quickest and most available answer.

Now, who do we hear more about in everyday life, loggers or police officers? Police officers are on the street, we see stories in the news or watch movies of cops involved in dangerous situations. Because of the familiarity and the quick way we can summon this information, we immediately assume police officers have a more dangerous job than loggers.

Contrary to popular belief, loggers are more likely to die on the job. Consider this: loggers are handling heavy and dangerous machinery to chop large trees, often working in remote areas, far away from medical attention. Doesn’t sound too safe, right?

TIP: Be willing to dig deeper into specific decisions to amass more facts before relying on the quickest conclusion your brain makes.

Can We Really Cope with 35,000 Decisions a Day?

We all make decisions, constantly. From deciding which pasta to buy, or which path to take at work, humans average 35,000 decisions in a single day. What happens when we’re bombarded with decision after decision to make? We usually end up tired and ready to throw our hands in the air and pick whatever takes the least effort. Sound familiar? Psychologists call this decision fatigue. It comes in a variety of forms, all of which impair our rational decision-making abilities.

If you made a large purchase, say a car, you may have felt overwhelmed by the warranty, upgrades and financing options. Decision fatigue is shown to ramp up after the buyer agreed to a set price and then is tasked with deciding their financing details. Instead of viewing all the information with a clear head, it’s more likely the buyer will buy extras they normally wouldn’t have, all to complete the tiring deal and call it a day.

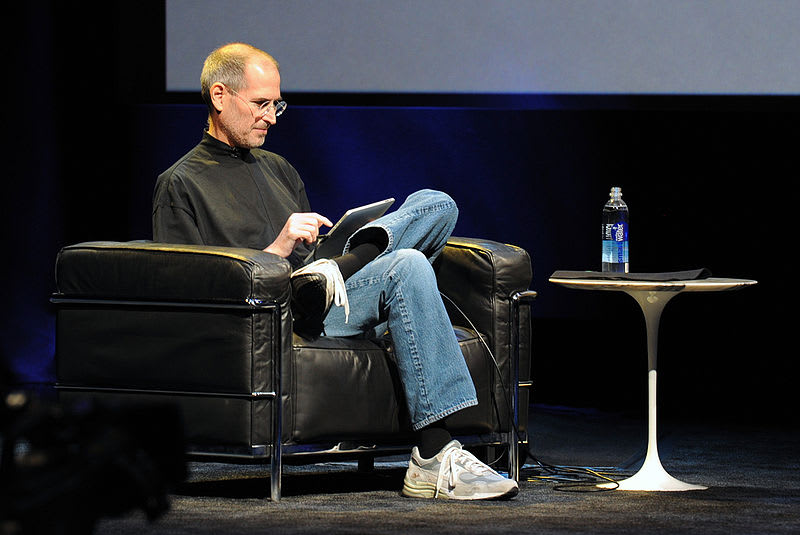

To tackle decision fatigue, think about Steve Jobs. Can you recall his signature look? Jobs wore a black turtleneck, jeans and New Balance sneakers, every day! While it seems eccentric to wear the same thing each day, it’s common practice for people in high-powered positions. With their overwhelming responsibilities and need to make large decisions, eliminating part of their routine frees up space in their minds to focus on more important tasks at hand.

TIP: Break the fatigue cycle in the moment with 5-10 minutes of downtime to give your brain a breather.

Does Optimistic Mean Less Realistic?

Picture this: your colleague asks you to pick up cookies on the way to work, and while you have a busy day, you estimate the errand should take around 10 minutes to complete. No big deal, right? In the end, it takes 25 minutes because there was a long line at checkout, extending your original estimate by 15 minutes. This is a fictional example, but can you remember a time that you committed to a task and it took you longer to finish than you originally thought

Known as the planning fallacy, this phenomenon affects our ability to measure the time it will take to do a future task. Even if you performed the same task in the past and know how long it took, it may not bear on your ability to properly estimate that same assignment in the future.

This is heavily influenced by optimism bias, a belief that negative things won’t happen to you, rather to other people. Another aspect of optimism bias in relation to planning fallacy is to focus on the best possible outcome of the future task, not taking into consideration potential pitfalls that may occur. A real life example is the Sydney Opera House, a project slated for completion in 1963 that took an additional 10 years to finish. The starting budget was set at $7 million and because of delays, it ended up costing $102 million.

TIP: Plan, plan plan! When tackling a big project, write out all the little steps it will entail to get a clearer idea of the time, costs and other details involved. Challenge your brain to ask what if, and brainstorm potential obstacles that may take your project off course.

Can You Can Learn toTrust Your Gut?

If our rational decision-making process is filled with biases, there is always another option—intuition. How many times have you heard the phrase, “go with your gut” or “follow your heart”? We commonly believe a gut feeling is our internal truth or the little voice inside of us meant to lead in the right direction. Digging deeper into the science behind intuition reveals a more complex system. Intuition depends on multiple factors that determine if it is good or reliable.

Intuition is a culmination of patterns we recognize throughout our lives, a way to identify or understand how things work. You might learn that when a traffic light is about to turn red and you check both sides of the road, you’re clear to cross. Or if a friend doesn’t return your calls, there might be a problem. While you may think you can sense these situations, they’re based on your familiarity and the tendency for them to repeat and offer the same results.

Successful intuition also relies on expertise. Say you’ve worked as a top salesperson for over 3 decades. You can quickly gauge which customers you can convert and the exact pitch that will work. Potentially viewed as good intuition, it’s born out of experience, long-term observation within a specific environment and a certain level of pattern-regularity.

.20191124154719.jpg)

Spot-on-intuition relies on receiving immediate and accurate feedback. Take Simon Cowell, the creator of the X Factor. He is famous for his harsh judgment and snap decisions on who has what it takes. Cowell may claim to know who will be famous, but it’s based on years of practice and tweaking his methods to determine what makes a performer successful. Lack of information, experience and unhelpful feedback render intuition less trustworthy. If you asked Simon to use his intuition to assess if an athlete has “star power,” his gut feeling may be less reliable. If someone is out of their comfort zone, they are not as prone to intuitively make the best decision.

TIP: Trust your instincts when confronting situations where you have more familiarity, expertise, and are within your realm of knowledge.

Good News: You Can Train Your Brain

Humans have hard-wired ingrained biases that affect our ability to make decisions. While the study of decision making is vast, there is always new research unveiling the complexities of the human mind. A rational mindset means understanding your limitations and your capacity to change and grow and create new habits to make better decisions. The more we grasp how our minds work, the better we can draw smarter conclusions, save our brainpower for more pressing decisions, and even trust our intuition.